JACKIE

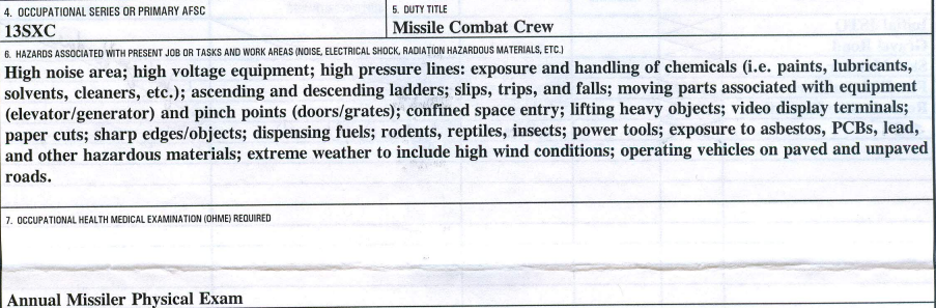

My name is Jackie. I was a Missile Combat Crew Commander from 2000 to 2004 serving in the, now-decommissioned, 564th Missile Squadron, Malmstrom AFB, Montana. I then served as an instructor in the 392d Training Squadron at Vandenberg AFB, California until separation in 2006. I completed over 200, 24-hour underground alerts at remote locations attached to Malmstrom Air Force Base, Montana. I am the “Missile Sister from another Mister” that Monte talks about in his story. I was diagnosed with Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL) in 2018 at age 42. In 2020, Veterans Affairs (VA) made the service connection between my cancer and exposure to asbestos while on alert. Fortunately for me, I still had a copy of the Air Force (AF) Form 55, Employee Safety and Health Record, signed in 2001, showing toxic exposures to chemicals, fuels, rodents, asbestos, PCBs, lead, and “other hazardous materials.” What’s not documented on this form are burning plastic-coated paper, radon, and possible biological exposure due to water intrusion and sewage.

Diagnosis

I was diagnosed with Stage 3, Grade 1-2, Indolent Follicular Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in April 2018. I had been experiencing a lot of stomach pain, body aches, hot flashes and was extremely exhausted. I was working full time while taking care of kids and a husband who was undergoing his own cancer treatment. A few years prior I had my gallbladder removed and figured these symptoms were just aftereffects, or my thyroid meds were out of balance, or that I was simply run down from stress and everything our family was going through. Eventually, I made an appointment with my primary care doctor for a physical. My doctor put me on some proton pump inhibitors and ordered a CT scan to rule out problems with my guts.

The CT scan results revealed an enlarged spleen and two slightly enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes. We weren’t super worried. I was run down, and maybe I had a virus or something; perhaps mononucleosis? I was asked if I wanted a lymph node biopsy and told it would be performed under anesthesia as well as CT-guided due to the depth of the lymph nodes. I agreed and had the procedure. I got the biopsy results while on a work trip and fell to my knees. How could I have cancer too? The doctor told me an oncology appointment had been scheduled for the following Monday. Turns out it was with my husband’s oncologist—the two-for-one special! We decided not to tell anyone until we determined how bad this really was. My oldest son knew right away something was wrong. We struggled over the weekend, crying, praying, hoping for the best.

I was told the “good news” was I had what the doctor called “lazy lymphoma.” The bad news was the disease was incurable and is a life-long condition unless it morphs into a more aggressive cancer. I was lucky that this was the best of all the bad outcomes. The cancer was so slow-growing that I would not require treatment right away. So, I was put on a “watch and wait” regimen. I was relieved but thought it was kind of ridiculous I would have to rely on my feelings to know whether I needed cancer treatment. So, I was supposed to go home and live my life. If I had swollen lymph nodes, drenching night sweats, and rapid weight loss, I was to let the oncologist know.

I was referred to a clinical research study at the National Institutes of Health under the Lymphoid Malignancies Branch (https://ccr.cancer.gov/lymphoid-malignancies-branch). This study has allowed me to be under continual surveillance via periodic blood tests, and CT and PET scans since 2018. If this lymphoma blows up into something bigger, they will be able to catch it during a scan or test. The lead doctor who is an expert in this field confirmed this was active cancer, that it was incurable, and would have to be monitored and managed for the rest of my life.

Navigating Veterans Affairs

Veterans Affairs is a mixed bag. The compensation side is completely separate from the healthcare side to avoid conflicts of interest. Your experience may vary depending on the contract provider you are assigned in the claims process. Navigating the VA claims processes, especially 12 years after military separation, is not for the faint of heart. I attempted to use the state Veterans Advocate, but there are so many veterans in my state, it was tough to get an appointment. I decided to complete the claim on my own through the VA website. It took a few weeks to gather the necessary documentation, write a cover letter, and connect the dots between the AF Form 55, test results, medical diagnoses, and service dates. I bought a sheet-fed scanner to digitize and make searchable my hundreds of pages of medical records.

I was hesitant to make the claim because of the awful experience I had filing my first claim after separating from the Air Force in 2007. I had gathered my claim documents the Disabled American Veterans had helped me prepare in the transition assistance class and met with a contract doctor. The doctor all but implied I was a benefits-seeking liar. He made me feel I wasn’t worthy of any compensation for my minor claims amounting to 10% each. Like I broke myself in the military. So, I had pretty low expectations of this new claim, especially since this was before the PACT Act.

I went to the new contract doctor sometime in 2020, about 6 months after submitting my claim through www.va.gov. I was so scared going into the appointment…scared the doctor was going to treat me like some hypochondriac, just like the last guy, but he didn’t. I was treated with respect and diligence. He was positive, attentive, and had reviewed all my records and detailed cover letter. Additionally, he had done some research through PubMed articles and judged there was a connection between asbestos and NHL. Based on his findings and recommendations, I was granted a temporary service connection. Apparently, a VA cancer claim is generally temporary because the law has determined that remission after treatment is equal to being cured.

My experience taught me the quality and attitude of your assigned contract provider make a huge difference in whether the VA will grant your claim, making the process highly subjective. The system and process worked for me, but for so many of our colleagues, the result is denied claims and/or indifferent treatment by people who are supposed to help.

I continue to augment my civilian medical care and my NIH oncologist team with specialists through the VA. To date, I have received excellent care through the Hunter Holmes MacGuire Hospital in Richmond, Virginia. I have colleagues who utilize their base hospital for care in other locations, and it seems the quality and level of care varies wildly from place to place and doctor to doctor.

Discovery of a Cluster

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) define a cancer cluster as a greater-than-expected number of cancer cases that occurs within a group of people in a defined geographic area over a specific period of time. I knew we had a lymphoma cluster when I was a young lieutenant in the 564th, but the study results in the early 2000s determined LCCs were a “safe and healthy working environment.” We had the normal missileer gallows humor when this came to light. Launch Control Centers were so gross—anything but safe and healthy. As soon as you got home from alert you tossed your clothes straight into the laundry because of the oily, briny smell. I honestly forgot all about lymphoma until I was diagnosed in 2018. Fast forward to 2021, when my heart broke seeing Monte and finding out he too had NHL. About a month later, I got more calls from the missile community and we all started connecting the dots—there was another cluster, this time though, it was showing up many years after we had all completed our missile duty.

I respectfully and formally requested the DoD Inspector General perform a comprehensive health and safety study of working conditions at Malmstrom AFB and ensure missileers had specific exposures permanently documented in their records. The AF Form 55 I had in my own files was nowhere in my AF Medical or Personnel Records. I also heard from colleagues from before and after my time that their own AF 55s, if they had them, did not document any toxic exposures. I went to the DoD because I was concerned the Air Force might rely on the previously published studies from the early 2000s—studies that I believe are deficient. The growing number of cancer-related health events documented by the Torchlight Initiative and the PCB results from the Air Force Missile Community Cancer Study validated and justified my request for an investigation and mitigation of toxic environmental exposures.

Time for Investment

Nuclear Deterrence has been the backbone of US Foreign Policy and Military Strategy since 1945, whether we like it or not. Unlike airplanes or submarines, the control centers of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles have not had a major replacement or safety/materials refurbishment since the 1960s. Sure the missiles have been replaced and new computers and consoles installed, but the basic plumbing, sewer, electrical, heating, cooling, and ventilation is still 1960s building technology—asbestos insulation, liquid PCBs, an old formula for cooling brine, sewage backups, etc. For too long, Congress and the Air Force have been content to coast on the Cold War infrastructure boom of the 1950s and 60s. Not only do we know those old materials are toxic, but as time goes by, the chemicals break down into new compounds with unknown effects. The time to build new control centers was at least 30 years ago.

Now, Sentinel promises to deliver new, modern control centers built with safer materials. I hope our stories push Congress and the Air Force to deliver Sentinel on or ahead of schedule so we can continue to protect our nation, give decision-makers options, and backstop our soldiers, sailors, marines, guardians and airmen. In the meantime, I’m choosing to trust the Air Force will take environmental monitoring seriously and mitigate the known toxic materials in the control centers for my fellow missileers pulling alert duty today and tomorrow.

I’m extremely proud of my missile service. Continuous nuclear alert mattered in my time and it matters every day in this crazy and broken world. Missiles gave me life-long friendships, decision-making opportunities, leadership experience and attention to detail skills that serve me today. This mission and our young missileers are vital to our national security. Let’s keep it that way and take care of those who stand the watch.

Great article, Jackie. I am honored to have served with you and hope you beat this thing.

One of the best crew partners I ever had, still smile thinking about the time we ran into each other at the Denver Airport.

Thanks for opening up about this Jackie. Your story helps us all!

Jackie! Thank you so much for sharing! It gives many of us a better understanding of many of the factors that lead to your kind of outcome, and a few of the potential symptoms to look out for. I’m proud of our time together and what a light you have been!

Thank you so much for sharing; giving a louder voice to the whispers. Your work and courage is applauded.

Thanks Jackie. I was also Deuce 87-90 (GLCM before that). I am curious on your thyroid issues since I am hypo (Hashimoto). I have heard in other posts that there was apparently a correlation with crew duty and higher instances of thyroid issues. Not as serious as cancer for sure, but something that I will live with the rest of my life. Saying a prayer for you and your family. Mac

Funny, I was diagnosed hypo while I was still on alert. The Flight Surgeon wouldn’t do the test and told me I was just fat. It was my gyno nurse practitioner that approved the full thyroid panel, including the antibody test. I was never told I had Hashi until later. There are a lot of missileers with thyroid problems.

So proud of you sister from another mister! You never know who will benefit from your words of wisdom.

Thank you for having the courage to share your story and shine a light on this issue. Your words may serve as inspiration for others to share their stories.

What is this Form 55 and how do we get one?

Darel, it’s a form we all signed and almost none of us kept a copy of. Jackie was fortunate to have had a mentor that convinced her it was important enough to keep. We all would have signed one annually confirming we were aware of the hazards encountered on the job. If you have more questions hit me up naidasmk@yahoo.com

Jackie, thank you for sharing your story and experiences. I appreciate you sharing how you navigated the VA process. Thanks for fighting for all missileers.

Jackie…keep fighting the machine for the next generation and your cancer. Thank you!

Jackie, I can’t believe I wasn’t tracking this better. I’m fully engaged now and thanks for talking with me offline. Thanks for all your efforts to help each and every missileer. While those years were not the highlight of my time in the AF, the people were. Keep up the good fight!

Jackie, I’ve been so remiss on comms…tracking all now… We should reconnect.

Jackie, thank you for sharing! One of the best Crew Commanders I had the pleasure pulling alert with!